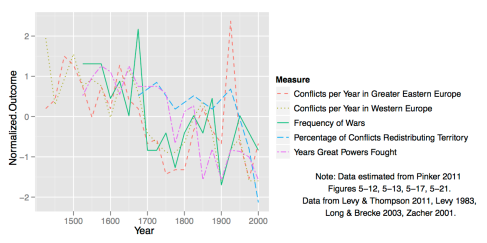

We live during an era of historically unprecedented peace. Whether we look over timescales of decades or centuries, wars have become less frequent. Figure 1 (data drawn from Pinker’s excellent new book, original sources include here and here) illustrates the downward trend in five measures. There are fewer Great Power wars, fewer wars in Western Europe, fewer years during which a Great Power war is ongoing, and less redistribution of territory after wars. Other trends, not as readily quantified, are evident. Countries no longer covet each other’s territory, or fear invasion and military coercion, like they have throughout most of history. National identities and aspirations are based less on martial glory, honor, and dominance. The relative absence of war, and especially Great Power war, since the end of WWII has been referred to as the Long Peace. As unbelievable as it may seem to readers of history, these and other trends suggest to many scholars that the Long Peace is likely to persist.

Figure 1

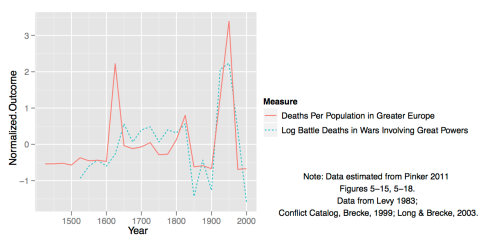

But unlike the robust decline in interpersonal and domestic governmental violence (again, see Pinker), it is not as obvious that the human costs of war have declined over time. Figure 2 illustrates two other important measures that don’t show a decline: except for the most recent few decades, battle deaths in Great Power wars and battle deaths as a proportion of population in Europe don’t show an obvious decrease. While recent decades do seem particularly peaceful given these long-term trends, we would hardly want to be complacent about this trend. Many previous decade-long spans of peace ended in devastating wars.

Figure 2

It may be, then, that wars have become vastly more destructive, especially with the invention of nuclear weapons, leading countries to be more cautious about their use of military coercion. The net costs of war on humanity, however, may not have decreased. The Cuban Missile Crisis ended with little bloodshed; however, it could have ended with hundreds of millions of deaths. Such a counterfactual would add a massive spike to the right end of the lines in Figure 2, and mute any discussion of a Long Peace.

Aggregate data like the above gives us some, but not a lot, of confidence that the world has moved beyond war. To probe the persistence of this Long Peace, it would be helpful to know what factors have made the world more peaceful, and the extent to which these factors are likely to persist into the future. Potential causes of the peace include increases in trade, democracy, the difficulty of coercing wealth, global empathy, Great Power stability, the empowerment of women, and the deterrent effects of nuclear weapons. Global Trends 2030 identifies a number of other factors pertinent to the future probability of war, including power transitions, declining US military superiority, resource scarcity, new coercive technologies (such as cyberweapons, precision-strike capability, and bioweapons), and unresolved regional conflicts.

Wars are rare, but when they occur they alter the course of history. Any projection of what the world will be like decades into the future needs to evaluate the probability and character of war, and especially Great Power war. This week we can look forward to a set of eminent scholars sharing their thoughts about whether the Long Peace will persist. Contributors include: Erik Gartzke, (UC San Diego), Benjamin Fordham (Binghamton), Joshua Goldstein (American), Steven Pinker (Harvard), Jack S. Levy (Rutgers), Richard Rosecrance (Harvard), Bradley Thayer (Baylor), and William Thompson (Indiana).

***

Allan Dafoe is Assistant Professor of Political Science at Yale University. His research examines the causes of war, with emphases on the character and causes of the liberal peace, reputational phenomena such as honor and tests of resolve, and escalation dynamics.

References

Pinker, S. 2011. The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined. Penguin Group.

Levy, J. S., & Thompson, W. R. 2011. The Arc of War: Origins, Escalation, and Transformation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Levy, J. S. 1983. War in the Modern Great Power System 1495–1975. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky.

Long, W. J., & Brecke, P. 2003. War and Reconciliation: Reason and Emotion in Conflict Resolution. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Zacher, M. W. 2001. The Territorial Integrity Norm: International Boundaries and the Use of Force. International Organization, 55, 215-250.

Pingback: “Global Trends”- CIA: Asia will as before be the center of economich development – Europa and US will losse their postions. Middleclass will be soon most important globally, but consume more and more, which will be a big problem for envi

Pingback: Linktipp: Zur Zukunft des “Langen Friedens” « Bretterblog

Pingback: The Long Peace: Systematic Trends and Unknown Unknowns | Global Trends 2030

Pingback: Predicting Peace’s Persistence | Breviosity

Pingback: The Hazards of Forecasting | Global Trends 2030

The concerns voiced here about the research are legitimate given the scope of the article, and we certainly would not want to be complacent on the subject in any case. On the other hand, I think Pinker’s underlying research and arguments address the questions raised pretty well (see The Better Angels of Our Nature reference).

I had just been thinking about exactly this subject when on a beautiful bike ride through Lithuania I came across a site of Holocaust mass graves in the forest: http://andreasmoser.wordpress.com/2012/08/12/holocaust-mass-graves-joneikiskes/ It made me think how close we are everywhere – at least in Europe – to brutal history. We are equally close to it in time. Two generations is not a long time. I tend to think we have mainly been lucky these past 70 years.

Pingback: DuckofMinerva: The Long Peace | Foreign Policy Review

Pingback: The Long Peace | So Superior

I think there are a few problems with this research. First, the focus is on Europe and the great powers to the exclusion of all other nations. This somewhat narrow outlook overlooks not only small scale conflicts, but also major ones including genocides in Rwanda, Darfur, and the ongoing eastern Congo war. Furthermore, it does not take into account the possibility of cold war as between Iran and Israel spilling out of control. Second, it is clear that peace is not simply the absence of wars and major conflicts, but also the availability of minimal conditions for human dignity.

For instance, some revolutions as in Saudia Arabia and Bahrain have been successfully repressed. Should we then conclude that peace has prevailed in these countries?

Political upheaval as well as major ethnic and religious conflicts are destabilizing the middle east, and making any peaceful coexistence, let alone decent economic conditions for hundreds of millions far from achievable.

Even in the west, extreme inequality and lack of fundamental rights as highlighted by the Occupy Movements and others do not give a foundation for a peaceful society.

Finally, the author points out that there are fewer wars between major powers which is true except that there is currently only one major power.

Somewhat narrow? It also avoids Vietnam, Korea, Iraq (x2) — somehow these US-led wars count as part of the “Great Peace” simply because the people were brown… I mean, outside Europe. And let’s not get into US-aided slaughters in Latin America, the half million dead Indonesians in 1965, Stalin’s millions, Mao’s millions, the list is endless.

It is only a “Long Peace” for the homelands of US and European countries (minus the former Yugoslavia — but that doesn’t count either, they are Slavs!).

I believe the phrase “Long Peace” came about because scholars of politics and history began to realize that something very unusual was happening, and they were looking for a name for it. One may object to the idea of a period including plenty of wars and deaths being called a “Peace”, but that is just a name which perhaps could be changed to something else. It does not change the fact that recent decades represent an extraordinary gap in direct wars between the strongest military powers on the planet. That gap is worth studying, to understand how it has come about and to try to keep it going.

I agree with Peter’s comment stating that “peace is not simply the absence of wars and major conflicts, but also the availability of minimal conditions for human dignity”. Actually, i’m a bit shocked that the authors didn’t mention equal chances on a good life, job, food, basic health care etc and similar levels of prosperity within a region as the basic condition to avoid conflicts.

In order to investigate why there are less wars, one should look for the reasons to start a war. If those reasons are absent, there will obviously be less wars. So i’m disappointed that the authors didn’t talk about any of this…

The site is 3 months old on the cunrret format, we are at 13,000 visitors so far, and we are working on new content, as both me and my brother have full time work its difficult to keep the content totally up to date and play pbbg’s to review. We are working on a few articles but they take time. We are happy to receive submissions if you want to help out.